Discussing rich text capabilities in a CMS is an exercise in compromise. Authors want the flexibility to be creative in their content. Developers want to ensure said content fits in the box. This can feel like fighting over the bed covers with a spouse: everyone initially means well, but things turn sour and we all wish for a bigger duvet. Or a more understanding spouse.

I believe the fundamental problem is one of control – for end users, control over content formatting, and predictability of the overall system. And for developers, control over content processing and rendering. Let’s crack open the rich text black box, and give everyone their fair share of the duvet.

Introducing Draft.js

Rich text pipelines usually process HTML, or a subset of it. With Draft.js, we instead work with a different content model that has been designed for rich text, and doesn’t rely on browser-managed HTML. Here is what you need to know:

- Draft.js is a framework for building rich text editors, powered by an immutable model.

- The content “source of truth” is separate from HTML rendered in the editor via

contenteditable(which has highly unreliable behavior between browsers). - It follows a fixed schema, with predefined formats (eg. bold) but also the opportunity to make custom ones.

- There are strong constraints on content structure – what is block-level formatting and what is inline, what can have data and how.

If you want to know the full story, have a look at Why Wagtail’s new editor is built with Draft.js.

The rich text pipeline

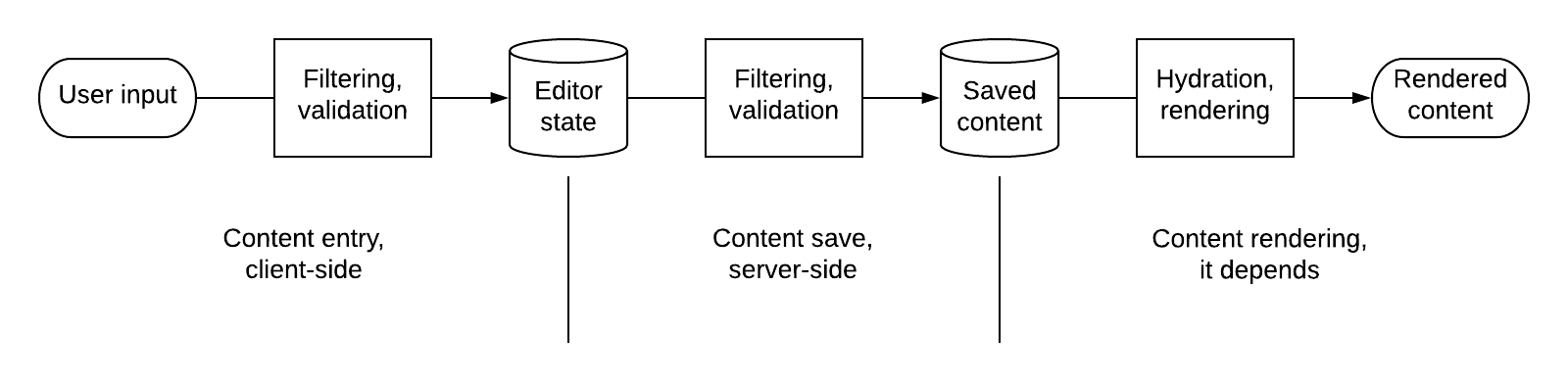

With the presentations out of the way, let’s have a look at how Draft.js affects the overall rich text pipeline. Here is a representation of rich text processing from content entry to rendering on the site:

In words,

- The user types into the editor, or pastes from Word.

- Content goes through filtering and validation rules before arriving in the editor’s internal state.

- On save, the content makes its way server-side, and potentially goes through more filtering and validation before being saved in the database.

- When displaying content, it is fetched from the database and potentially goes through a hydration / rendering step.

This isn’t a simple process. The fundamental problem is that rich text is generally unstructured, lacking in semantics beyond those of HTML. We don’t want to give users the freedom to use arbitrary HTML though, far from it. Let’s see how Draft.js helps.

Content filtering and validation

First off, why are there two filtering / validation steps in the diagram above? It seems rather wasteful! Unless, that is, the editor couldn’t be trusted with its content validation, and a second step was required to whitelist all formatting. This is exactly what Wagtail did before we switched to our Draft.js editor.

Here is a GIF illustrating the popular “paste from Word” workflow with Wagtail’s previous contenteditable editor:

Pasting rich text preserves a lot of unwanted or irrelevant styles, and there is no indication whatsoever that the content is problematic. Saving the content and reloading the page, we see the server-side filtering kick into action and – surprise – reveal Microsoft Word metadata and styles (wich is plain gibberish for a user). Even if that was properly removed, the rich text still contains unwanted formattings – subscript and superscript in this case.

By contrast, here is the Draft.js equivalent:

No need to waste time reloading the page, all of the filtering happens on paste, in the browser. This is possible because:

- The structured, fixed-schema content model is separate from contenteditable’s HTML. It is impossible to enter content that does not respect this schema.

- A formats whitelist filters out all of the content that respects the schema, but is not enabled in the editor.

- Draft.js comes with APIs to programmatically manipulate content, allowing further arbitrary processing.

Have a look at the Draft.js filters that power our editor to see how this works under the hood.

What about validation? For rich text, this usually means calculating some metrics on the content, like its length against a set maximum or minimum. This could be be hard if the content was HTML, and as a result developers often prefer to calculate string length including the HTML formatting, leading to a bad user experience.

There again, Draft.js having a fixed schema and an API makes this much simpler. Here is an example, calculating the plain-text length of the content:

const contentLength = content

.getBlockMap()

.reduce((total, block) => block.getText().length, 0);

Hydration and rendering

The content is now filtered, and saved in the database. Now we want to render it on a page! This is where Draft.js shakes up the flow quite a bit: we most likely want to render the content as HTML, so we need to first convert it. We also need to hydrate the content – provide it with external data that it requires, eg. replacing a reference to an image’s id by the actual image’s src and alt. Note that this hydration step would be required even if the content was stored as HTML.

The Draft.js -> HTML conversion may seem like extra overhead, but its impact will be minimal compared to data retrieval for the hydration. Additionally, it provides us with an opportunity to customise the front-end HTML our users will look at, for example:

- Adding classes to list items,

ulandoltags so you can use your favourite CSS architecture or methodology. - Automagically making all links pointing to third-party sites open in a separate tabs by adding

target="_blank"on theatags.

In practice, the API allows completely arbitrary rendering. It comes from the Draft.js exporter, and is heavily inspired by React’s createElement (what powers JSX):

# Basic example – let’s render all ul tags with an extra BEM class.

BLOCK_TYPES.UNORDERED_LIST_ITEM: {

'element': 'li',

'wrapper': 'ul',

'wrapper_props': {'class': 'list--bullet'},

},

# For ols, we want more control. Let’s add the nesting level as a class.

def ordered_list(props):

depth = props['block']['depth']

# This will create an ol tag like this:

# <ol class="list--numbered list--depth-1"></ol>

return DOM.create_element('ol', {

'class': 'list--numbered list--depth-{0}'.format(depth)

}, props['children'])

# Finally, we said we want our links to open in a separate tab when they point at external sites. Easy!

def link(props):

attrs = {

'href': props['url']

}

# If the URL does not start with /, add a target attribute.

if props['url'][0] != '/':

attrs['target'] = '_blank'

return DOM.create_element('a', attrs, props['children'])

Isn’t that exciting?! Unfortunately (insert sad face emoji here), this isn’t fully hooked up in Wagtail just yet. For content storage and rendering, Wagtail still uses its own HTML-like / XML representation. There is an open feature request to develop this further – feel free to chime in with your thoughts.

Have a look at the Draft.js exporter that powers our editor to learn more about the rendering API.

Beyond rich text

With the help of Draft.js, we are bringing more structure and semantics to rich text, and making rich text more reliable for end users. This doesn’t mean that developers should start using rich text for all content. Wagtail’s StreamField still is a wonderful medium. Plain text also has a bright future.

However, beyond the rich text pipeline, there is another area where Draft.js helps a lot: building better user experiences for content authors. This could be as simple as having a reliable way to measure the length of written content, or calculating other useful metrics like reading level. Or simply converting “quotes” into their “smart” equivalent, to make your site’s microcopy shine even brighter. All of those features could (and should) be available on plain-text content, and here as well Draft.js and its programmatic API could help tremendously.

Draftail already does quite a bit in this direction, in particular with its keyboard-centric control, and we’ll explore future possibilities in an upcoming blog post.